Winnipeg Transit has noted that, during rush hour in Winnipeg, there is an average of 1.2 persons per car. At that rate, 100 cars and 550 metres of traffic lane are required to accommodate 120 people. Only 2 buses and 25 metres of traffic lane can do the same job (1), reducing congestion, noise and greenhouse gas emissions by over 90%.

Winnipeg Transit has noted that, during rush hour in Winnipeg, there is an average of 1.2 persons per car. At that rate, 100 cars and 550 metres of traffic lane are required to accommodate 120 people. Only 2 buses and 25 metres of traffic lane can do the same job (1), reducing congestion, noise and greenhouse gas emissions by over 90%.

Public transportation saves more than time, space and fresh air. About 1,300 people are employed by public transit in Winnipeg.

Taking transit offers commuters freedom from:

- Car-related expenses – The Canadian Automobile Association reports that the average annual cost to operate a car is $7,500, (2) whereas a Winnipeg Transit bus pass costs about $1,040 (3) for an entire year.

- Parking hassles – Finding parking at sporting events and cultural events can be tough. Sometimes the walk from you car seems as long as the drive that brought you there!

- Traffic – Look at bus commuters. They are a pretty relaxed bunch. Someone else is dealing with driving. Transit users can also visit local cafes, bakeries and newstands before being carried calmly to their destination.

“Human Transit: How clearer thinking about public transit can enrich our communities and our lives”

“Human Transit: How clearer thinking about public transit can enrich our communities and our lives”

Jarrett Walker’s book “Human Transit: How Clearer Thinking About Public Transit Can Enrich Our Communities and Our Lives” does an excellent job of telling us how to create a public transit system that satisfies people.

We have summarized what we think are the key points in that book below.

You can also download and print a PDF of this summary.

The challenge

The core challenge of transit design is how to run vehicles so that people with different origins, destinations, and purposes will choose transit as their preferred mode of transport. Successful transit systems are simple (I don’t have to think about it.) and dependable (I can rely on it.) for riders.

Potential transit riders have 7 demands

“Transit has to exist when you need it (span), and it needs to be coming soon (frequency).” These are riders’ seven demands: (Ch2)

- It takes me where I want to go

- It takes me when I want to go

- It is good use of my time

- It is good use of my money

- It respects me by providing safety, comfort, and amenities

- I can trust it

- It gives me freedom to change my plans

Focus on frequency and span

“Speed is worthless without frequency.” Frequency has a direct role in meeting 4 of the 7 transit demands above. Transit-intensive cities pursue the following fundamental elements:

- Focus on ridership – City policy makers need to make ridership goals, rather than coverage goals the system’s overarching direction – and make their decision known to Transit planners and support them as they pursue this objective.

- Focus on all-day travel (i.e. span) – Transit gets more crowded at peak and buses get more frequent, but the basic pattern of the network is there all day and into the evening, 7-days a week

- Have extensive segments of exclusive right-of-way – This means corridors restricted only to transit – not just Rapid Transit lines but on-street transit lanes. The bus can be preferable to cars during rush hours (even if you have to stand on the bus) if your trip is shortened by priority lanes and signals.

Simple, direct routes

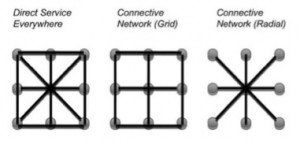

Encourage simple, direct routes with easy connections – If you avoid connections you sacrifice frequency, span, and simplicity. A connective network covers the same area with far fewer routes. People are not afraid to make connections from one bus to another if

Encourage simple, direct routes with easy connections – If you avoid connections you sacrifice frequency, span, and simplicity. A connective network covers the same area with far fewer routes. People are not afraid to make connections from one bus to another if

- buses are frequent of (especially on main routes).

- connection points are physically constructed to support connections

- bus routes are timed (i.e. pulses) to support connections

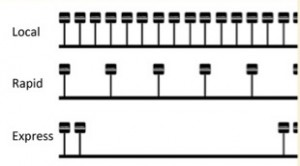

Stop spacing – Create routes with consistent stop spacing. Clearly distinguish between local, rapid, and express. (Ch5)

Stop spacing – Create routes with consistent stop spacing. Clearly distinguish between local, rapid, and express. (Ch5)

Simple Grid – Create a simple grid of high-frequency routes. In an ideal grid system, everyone is within walking distance of one north-south line and one east-west line. So you can get from anywhere to anywhere, with one connection, while following a reasonably direct L-shaped path. (Ch13)

Frequent Network Maps (and branding) – (Ch7) Answer the question: “I am someone who likes to use transit and would love to rely on it more, but I’m just too busy to be waiting a long time or worrying about whether service quits running at 7 PM. Where can I go on transit? Show  me the network that is useful to me.” Here are some examples:

me the network that is useful to me.” Here are some examples:

Easy connections

Connections reduce network complexity. Connections buy frequency without increasing operating cost. (Ch12)

- Clock-based timing – Design routes to reach stops on even divisions of the hour (e.g. hourly, 1/2 hour, 1/4 hour) (Ch13)

- Pulses – Coordinate schedules so buses from many routes come together at a central point. (Ch13)

- Connection hubs – Design connection hubs for ease of connection and to address drivers’ needs but also as commercial plazas. Connection points can be logical places to invest in transit-oriented development. (Ch13)

Other points

Pedestrians are important – “Virtually every transit rider is also a pedestrian, so transit ridership depends heavily on the quality of the pedestrian environment where transit stops.” (This also applies to cyclists.) (Ch1)

Chokepoints – “For car traffic, chokepoints are a problem, but for transit they are opportunities.” 1) They create opportunities to connect between lines, 2) they allow transit-only lanes to offer an advantage. (Ch4)

Transit-unfriendly suburbs – It is possible to provide transit service to suburbs with labyrinthine streets by providing frequent service routes adjacent and pedestrian and cyclist cut-throughs to get to the stops. Locate a transit-oriented urban center at the stop. Locate urban centres in a logical direct path with several other major destinations. (Ch14)